The Curious Case of the Missing Bust

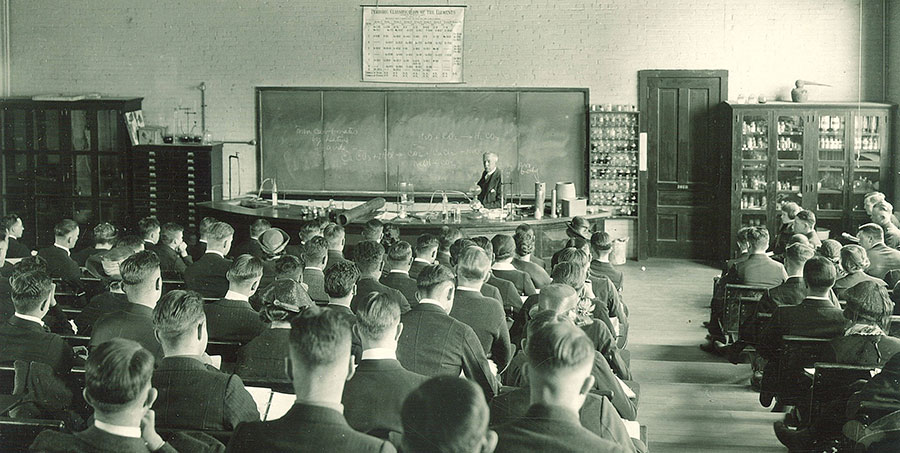

Photo: Frederick W. Kent Collection of Photographs, UI Special Collections

University of Iowa professor Elbert W. Rockwood gives a lecture in the 1930s in the Chemistry Building.

Photo: Frederick W. Kent Collection of Photographs, UI Special Collections

University of Iowa professor Elbert W. Rockwood gives a lecture in the 1930s in the Chemistry Building.

Police divers were combing the icy Raisin River in southeast Michigan in January 2001 when they spotted a strange figure. There, amid the murk and muck, was the upper torso and head of a mustachioed man, hair neatly parted down the center, in a necktie and academic robe.

Michigan State Police had been dredging the riverbed for discarded evidence from a robbery. Instead, what they pulled from the water was an old bronze bust, 2 feet tall and about 60 pounds. The face wasn't familiar to police in Michigan—or anyone else living in the 21st century, for that matter. Authorities could, however, decipher the signature etched into its base: “E.W. Rockwood.”

Back at the crime lab, a Michigan State Police employee searched for the name online and came up with a hit. It seemed that the man with the mustache was linked to the University of Iowa's history. She contacted the State Historical Society of Iowa, which sent over a Rockwood signature from its archives. It was a match.

But questions remained. How did the statue of an Iowa City academic end up in the bottom of a river 450 miles away? Just how long had it been there? And who heaved it in?

The bust of Elbert W. Rockwood, which was reinstalled in the Chemistry Building earlier this summer, disappeared under mysterious circumstances in the 1980s.

The bust of Elbert W. Rockwood, which was reinstalled in the Chemistry Building earlier this summer, disappeared under mysterious circumstances in the 1980s.

A century earlier and a couple states west, the living, breathing Elbert W. Rockwood (1895MD) was one of the most recognizable faces at the State University of Iowa. A distinguished professor of chemistry and toxicology, Rockwood had likely taught more students than any other professor since the founding of the university, the Iowa Alumnus wrote in 1924. Rockwood, who came to the university in 1888, was the first director of the university's hospital and established what's believed to be the first courses on physiological chemistry in this part of the country. He served as head of the Department of Chemistry from 1904 to 1920, growing the department from 50 students to 575 enrolled in courses.

In fact, Rockwood was such a popular lecturer that a group of his former students commissioned a bronze bust in his honor in 1930—no small expense during the Great Depression. To capture their professor's likeness, they hired a noted Chicago sculptor named Alice Littig Siems (1919BA), who also had deep ties to the university. An Iowa City native and daughter of a UI physician, Siems studied at the prestigious Chicago Art Institute after earning her degree at the UI. She was the protégé of renowned sculptor Lorado Taft, a frequent lecturer at the UI who had met Siems on a visit in 1921 when she was working as a museum assistant in the zoology department. Taft was so impressed by her artistic talent that he invited her to work in his Chicago studio.

Siems became one of the more prominent sculptors of her era and exhibited work at galleries in New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia. She created portrait busts of many well-known figures, including Taft and poet Carl Sandburg. Several UI leaders also sat for Siems, who sculpted bronze likenesses of university president Walter Jessup (34LITTD), Graduate College dean Carl Seashore (27BSAS), and political scientist Benjamin Shambaugh (1892BPH, 1893MA), among others.

“Each head is a forceful portrait,” the Chicago Tribune once wrote of Siems' work. “These portraits stand out, each one alone, complete, able, and distinctive substitutes for the men who sat for her.”

Rockwood remained on the faculty until his death in 1935, but his bust became a longstanding presence in the Chemistry Building.

Though not a permanent one, as it turned out.

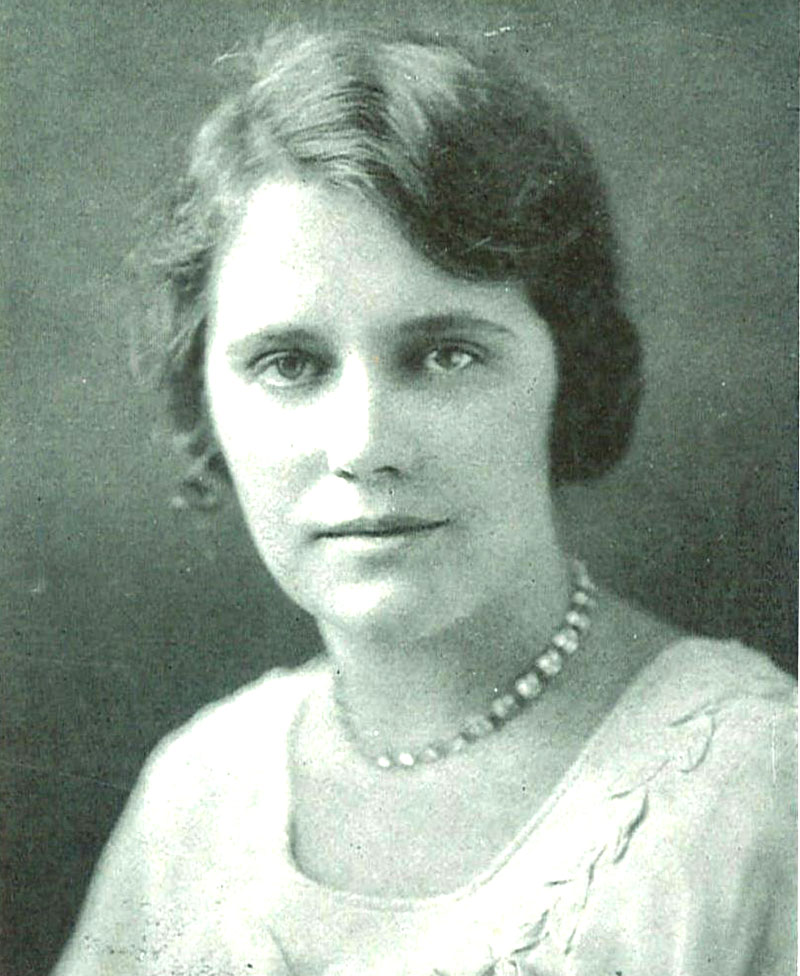

Photo: 1932 Hawkeye yearbook.

Alice Littig Siems, a prominent sculptor last century, graduated from the State University of Iowa in 1919 and created busts of several university dignitaries, including E.W. Rockwood.

Photo: 1932 Hawkeye yearbook.

Alice Littig Siems, a prominent sculptor last century, graduated from the State University of Iowa in 1919 and created busts of several university dignitaries, including E.W. Rockwood.

Students who frequent the Chemistry Building may be as science-minded as they come, but even they have their superstitions. For decades it was tradition for test takers to rub the old bust perched outside the lecture hall for luck. In fact, so many nervous hands had patted the sculpture that E.W. Rockwood's nose was said to have developed a distinctive shine to it.

The bust also was a favorite target for pranksters. On several occasions the sculpture went missing from its 5-foot pedestal only to reappear a few days later. Fraternity members were the presumed culprits. In the mid-1980s, the bust vanished yet again—only this time it never turned back up. “It disappeared so often that the last time it disappeared, I don't think anyone really noticed,” chemistry professor emeritus Jack Doyle told a reporter years later. Eventually the empty pedestal was removed, and as the years passed, memory of Rockwood faded.

That is, until the 2001 phone call from Michigan. The bizarre story of a UI statue found among the fish in Michigan made headlines in Iowa. The Gazette dubbed it “heads-up investigative work,” while the Des Moines Register reported that Michigan authorities weren't interested in prosecuting anyone involved in the decades-old caper. “We just want someone to give up the information so we can find out what happened,” a state police employee said. Soon after the Register story ran, an anonymous caller from Des Moines told Michigan police that fraternity members swiped the bust in fall 1984 and eventually dumped it in the Raisin River. He provided no further details.

The statue had been found in waters near Adrian, Michigan, home to Adrian College and Siena Heights University and about 35 miles away from the University of Michigan. It's plausible that the bust's abductors had dumped it while visiting fraternity brothers in Michigan. Or perhaps Michigan fraternity members swiped it from a house in Iowa City and brought it back home before discarding it.

Regardless of how it ended up in Michigan, the sculpture was grimy but otherwise in fine shape for sitting at the bottom of a Lake Erie tributary for years.

After its discovery, Michigan authorities shipped the bust back home to Iowa City, where the UI Museum of Art took possession of it for restoration. For various reasons, however, the statue was never put back on display. Early on, there was talk of raising money for a new marble pedestal, but the idea proved too costly. The Chemistry Building, which opened in 1922 while Rockwood was leading the department, also underwent major renovations after the sculpture's return, further delaying its reinstallation. Then, the flood of 2008 swamped the old art museum, and the bust and thousands of other UI-owned art pieces were evacuated and placed into emergency storage. Once again, the bust was all but forgotten.

Brenna Goode, a departmental administrator, first heard the story of the missing sculpture from a longtime faculty member when she joined the chemistry department in 2010. Goode was curious and inquired about its whereabouts over the years. Her persistence paid off; the bust was located among the items mothballed by the museum after the flood, and plans took shape earlier this year to return it to its rightful perch.

The department recently commissioned a new plaque and pedestal. Then in late July, after its strange journey and 34-year absence, the memorial to E.W. Rockwood made its homecoming to the Chemistry Building, no worse for the wear. When students return for classes this fall, Rockwood will be keeping watch just inside the building's main entrance, ready to be rubbed by a new generation of chemists.

“It's great to see the Rockwood bust finally returned to its prominent place in the Chemistry Building,” says Edward Gillan, an associate professor of chemistry who has written about the department's history. “Our alumni honored Rockwood's teaching legacy with this bust. I hope that its return inspires current and future chemistry faculty to sustain the Rockwood teaching legacy.”

One important alteration has been made to the statue, it should be noted. The bust is now fixed to the pedestal, and the pedestal is secured to the floor and wall. “No one should be able to get at it without some significant effort,” laughs Goode.

Do you remember the Rockwood bust or its disappearance? Email [email protected].

Department Head

A new plaque now accompanies the bust of E.W. Rockwood, which was reinstalled last month just inside the main entrance of the Chemistry Building. The plaque reads:

“Dr. Rockwood joined the teaching staff in 1888 and pioneered laboratory instruction in physiological chemistry at Iowa. Head of the Department of Chemistry from 1904 to 1920, he served as professor until his death. In 1890, on his return from studying with German master of physiological chemistry Felix Hoppe-Seyler, three medical students asked Dr. Rockwood to introduce them to the field. He later said, ‘Our work together on Saturday afternoons... was the beginning, at least west of the Mississippi, of what is now called biochemistry.'”